Ben Adams won a share of the competition funds

HOW to farm sensitively with the environment while minimising inputs and maximising outputs is what makes Ben Adams tick.

It is this drive, along with an existing passion to trial new ideas on farm, which encouraged him to enter and ultimately win the Journey to Net Zero competition run by the School of Sustainable Food and Farming.

He has used his funding to develop intercropping trials at the family farm near Bicester, Oxfordshire.

"I do quite a lot of trials anyway and I really just needed to upscale them to find out what works," he explains.

Ben's interest in intercropping - where two or more crops are planted and harvested together - stems around boosting output.

"If I am growing two crops, hopefully I can get at least a 60 per cent yield off both of them, compared to the 100 per cent yield I would expect in one field. "The idea is that if it is on the same area that creates 120 per cent overall. So, you are gaining a larger output from a smaller area of land."

Marrying this with a ‘sensible' approach to inputs also makes sense to keep costs under control and help the environment, however, ultimately it has to stack up financially.

"We are looking very much at costings and farming profitably without the Basic Payment Scheme, while farming sensitively with the environment."

The mixes

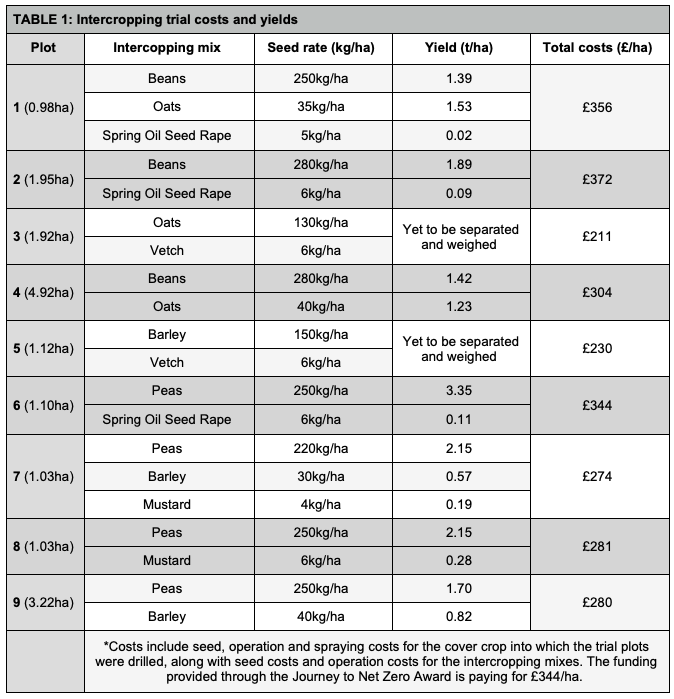

Two fields totalling 16.5 hectares (41 acres) were put aside for the intercropping trials. The mixes (see Table 1) were direct-drilled into a cover crop including a diverse mix of species, such as buckwheat, phacelia and linseed, which had been established after wheat.

A harsh winter meant not much of the cover crop mix survived and the ground was mostly cereal weeds and volunteers. These were sprayed off with glyphosate and then drilled with the trial mixes in April.

No additional inputs, such as nitrogen, herbicides or fungicides, were used on the intercropping plots thereafter. The intercropping mixes were selected to give a variety of combinations.

However, each mix was designed to include a legume with the aim of leaving some nitrogen behind for the following crop. All in all, seven different crops and 15 different varieties were used in varying combinations across the plots.

Three complementary but different varieties of beans, peas, oats and barley were selected to create diversity and added resistance to disease to avoid the need for fungicides. One variety each of spring vetch, white mustard and spring oilseed rape were used due to the fact these are niche crops with less choice.

Growing season

The performance of each mix throughout the growing season varied from week-to-week with some crops looking good one week and not the next. But there were some stark visual differences between plots with the spring oilseed rape proving a headache for Ben from start to finish.

He says: "The crop looked like it was going to set seed and then decided to flower again and never properly matured. As a result, there was very little of the crop left at harvest, leading to the decision never to grow it again.

"The vetch also did not perform that well, but that was partly linked to a calibration error at drilling leading to high rates on one plot and lower rates on the others. Both plots with the vetch did not look as good, especially with the barley as it requires early nitrogen to really get it going and it does not really get much from the vetch."

There were also marked differences in weed burden between plots.

"Definitely when cereals were included in the mix, the weed burden appears to be lower. I was not expecting that."

The weed burdens in the noncereal plots did create challenges, particularly as there was no option for desiccation.

Wet crops

The crops were also wet and required drying with the trash. In fact, weed burden and separation were identified by farmers as the top barriers to intercropping at a number of farm walks hosted by Ben throughout the year. Separation proved to be a justified concern at harvest, which took place at the end of August and start of September.

This was a particular issue in mixes including similar seed sizes such as vetch, oats and barley. Most mixes with varying seed sizes could be separated on-farm using a three-screen rotary cleaner. However, a colour sorter will need to be hired at a cost of about £250/ hour to sort the mixes with vetches, oats and barley, hence why yield data is not yet available (see Table 1).

Ben reflects balancing costs will always be there when intercropping, but they will be diluted when intercropping on a commercial scale, rather on small trial plots. Any of the seeds produced which cannot be sold as a cash crop, such as mustard or vetch, will be used in cover crop mixes or winter bird seed mixes on-farm.

If you buy them it is a few thousand pounds per tonne, so if you are growing them, that is quite a saving," he says, adding that intercropping may also be of interest to livestock producers who could wholecrop and feed the mixes.

Profit per tonne of each intercropping mix is yet to be calculated. However, he believes the results are positive as a whole.

The low input intercropping approach used also brings potential income benefits from the Sustainable Farming Incentive, which may act as an additional incentive to producers.

Next step

The next step is to plant the trial fields with winter wheat. Then they will then go back into the intercropping trials in the third year, using a combination of mixes which worked well this year. Ben has yet to decide what these will be, but oilseed rape will not be used and he may trial a combination of mustard and vetch. Mustard performed well this season and, as the seeds are of differing size, they will be easier to separate."

ABOUT THE JOURNEY TO NET ZERO COMPETITIONTHE Journey to Net Zero is a School of Sustainable Food and Farming competition, which was launched in summer 2022. A £50,000 funding pot was put up for grabs as part of the competition, which aims to help fund scalable, sustainable farming systems or processes which will have a positive and measurable impact on how the winners farm. More than 60 applied, with eight shortlisted for a Dragon's Den-style event at Harper Adams University - the home of the School of Sustainable Food and Farming. Four winners were selected and were awarded grants of £10,000-£17,000. Their progress will be followed, with the aim of using their experiences to serve as wider learning for others in the industry. |