What's the problem?

The liver fluke, Fasciala hepatica is a parasitic flat worm that affects sheep, cattle and other grazing animals, and is often associated with wetter pastures.

However, fluke is no longer just a problem for the wetter, western areas of the UK and Ireland. Movement of animals and a generally wetter climate - even in traditionally drier, eastern areas - means that liver fluke infection is a major threat across all sheep farms. Recent studies found that 50% of lrish1 and 54% of Welsh2 sheep farms were positive for fluke infection.

Liver fluke infections can cause either, acute, subacute or chronic disease in sheep. Outbreaks of acute disease can be very impactful as it can cause sudden deaths in a large proportion of affected sheep. However the effects of all forms of disease can be costly, causing; ill thrift and reduced growth rates in lambs and poor reproductive performance and reduced milk production in ewes.

Liver Fluke Fact Sheet

Life Cycle

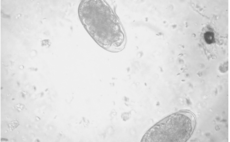

The adult stage of Fasciola hepatica lives in the liver of infected animals, specifically in the bile ducts. Adult flu Ice lay thousands of eggs each day which are passed along the bile ducts and into the intestine and excreted in dung. Once outside the animal, eggs can survive for several months, but usually hatch within 2-20 weeks depending on soil type and ambient temperature.

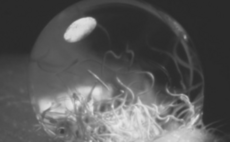

Freshly hatched larvae, called miracidia, depend on a secondary host - the mud snail Galbo truncatula - to complete their life cycle. After entering the snail, the miracidia multiply several times and develop into cercariae. After around six weeks the developed cercariae exit the snail and attach to blades of grass on the pasture, where they form cysts, called metacercariae, ready to be ingested by grazing animals. Each individual miricadium can produce hundreds of cercariae, meaning pastures can become rapidly contaminated.

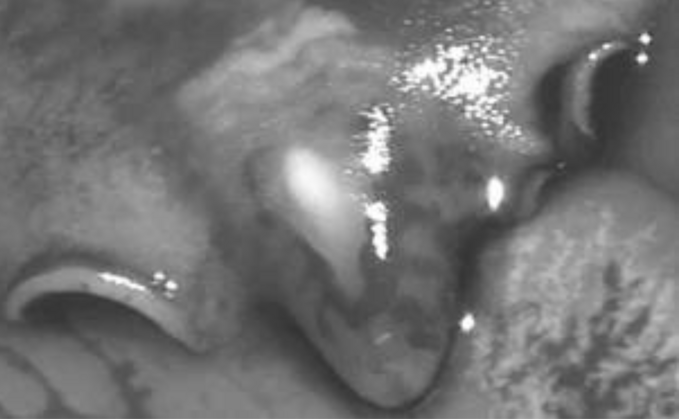

After ingestion by the host the cyst breaks open to release the immature liver fluke. This migrates through the animal's gut wall and abdominal cavity to the liver. The maturing fluke tunnels through liver tissue, enters the small bile ducts, and eventually reaches the large bile duct where it develops into an egg-laying adult, to complete the cycle. Without appropriate treatment, adult liver fluke can survive in sheep for many years.

Why does it matter?

Animals do not develop protective immunity to liver fluke, and there is no vaccines available for the prevention of fasciolosis (liver fluke disease). Unless an effective treatment programme is implemented on affected farms, sheep may suffer from clinical disease and reduced productivity.

Outbreaks of acute fasciolosis typically occur during late summer and autumn when pasture challenge is at its highest. It occurs when large numbers of juvenile fluke migrate through the liver, causing extensive damage to the tissue and blood vessels. Affected sheep rapidly become weak and may die suddenly.

Acute disease has a major negative impact on sheep welfare and productivity. The cost of diagnosis, treatment, dead losses and disposal costs have a negative impact on farm profitability. In addition to this, managing outbreaks of acute fasciolosis can be distressing for farmers.

Chronic fasciolosis is less likely to result in death, but can cause significant production losses. The disease occurs three to five months after ingestion of fluke cysts (metacercariae) from pasture

How to control liver fluke

Liver fluke control programmes must take into account the farm history, topography, geographical location and the prevailing weather.

Most programmes will rely heavily on flukicidal treatments, but due to the risk of selecting for triclabendazole-resistant fluke it is important that other active ingredients and techniques such as pasture management and good quarantine procedures are also included.

The choice of flukicide and frequency of use will depend on the level offluke cha llenge, the time of year, and the management and husbandry systems on the farm.

Diagnostic testing can he lp assess the need for flukicide treatments. To get the most out of this approach it is important that the most appropriate test is used and that the results are correctly interpreted.

■ Faecal samples can be tested for the presence offluke eggs. A positive fluke egg count indicates the presence of a chronic, adult fluke infection but does not provide information on the earlier, immature stages. Faeces can also be tested for coproantigen, a protein secreted by the liver fluke. This test can detect the presence of liver fluke around

2- 3 weeks before they reach maturity and begin to lay eggs. Both tests can also be used after treatment has taken place, to assess efficacy of the active ingredient.

■ Blood samples can be tested for the presence of antibodies. A positive resu lt indicates that an animal has been exposed to the parasite, however antibody levels will remain elevated after treatment.

■ Post-mortem examination can conclusively diagnose liver fluke infection. Similarly, abattoir feedback can provide valuable information on farm level fluke dynamics and the effectiveness of control measures.

Treatment

Treatment strategies should take into account farm-level risk factors and climatic conditions. Regional fluke forecasts such as those prepared by NADIS in the UK and the DAFM in Ireland can also provide useful guidance on seasonal risk.

Product selection should be based on the stage of fluke most likely to be present at the time of treatment; acute fasciolosis is generally seen during the late-summer and autumn, whilst sheep are more likely to be affected by chronic fasciolosis during late winter and spring, from January to April.

Most flukicides on the market are effective at killing adult liver fluke and are therefore suitable to control chronic fasciolosis.

However, triclabendazole is the only compound that will treat the early immature fluke that are the cause of acute fasciolosis.

Resistance to triclabendazole is a real threat to the sheep industry so appropriate steps must be taken to use it on ly when needed, to preserve its long-term use. Repeated and frequent use of triclabendazole should be avoided, and alternative active ingredients, such as nitroxynil, should be used wherever possible, particularly in late winter and spring when the risk of acute fasciolosis is lower and treatments are targeted at the later fluke stages.

Combination fluke and worm products should only be used when there is an identified need to treat worm species at the same time as fluke. Anthelmintics should be targeted specifically at the parasites to be treated, to avoid selection for resistance.

As always, alongside product selection, correct dosing and administration is key to ensuring that treatment is effective.

Pasture management

Spring-born suckled calves are exposed to lower levels of gutworm challenge in their first grazing season as the bulk of their nutrition is derived from their dams' milk until later in the grazing season.

Autumn-born calves, once weaned and turned out the following spring, are at risk of PGE in their first grazing season. Turning calves onto ‘rested' pasture (i.e. not grazed by cattle for at least one year) during their first year at grass can help to reduce the risk.

Bought-in stock

Purchased cattle with an unknown treatment history could be carrying significant worm and fluke burdens, and may introduce resistant parasites and other diseases. A quarantine protocol, developed with a vet, should be consistently implemented.

Anthelmintics

Wormers can be used to remove gutworm infections, which will also help to reduce pasture contamination. To ensure the most effective approach is taken, it is essential to understand both the parasite life cycle and the properties of the anthelmintic selected for treatment.

In recent years targeted approaches to treatment, based on farm level risk factors have been increasingly adopted. These approaches aim to reduce unnecessary treatments whilst still achieving effective parasite control. Pooled faecal egg counts can be used to determine the worm burden of groups of young grazing cattle; whilst regular weighing to identify animals that are not achieving growth targets can provide an assessment of the need to treat individual animals.

Strategic early season worm control using timed treatments of cattle during their first grazing season can provide an effective approach to controlling gutworm burden whilst still allowing natural immunity to build. In order to achieve season long control using this method, cattle must remain set-stocked, or only be moved to ‘safe' pasture such as aftermath.

Housing is also a key time for treatment: removing the worm burden, including encysted larvae, will help to maximise productivity and growth over the winter period and reduce the risk of disease due to type 2 ostertagiosis.

The choice of anthelmintic product will depend on farm history, animal and pasture management strategies and whether there is a risk from other parasites such as liver fluke.

As with the use of all medicines, the most appropriate anthelmintic should be determined following discussion with a vet or animal health advisor.

References

- Pia Munita et al (2019) Liver fluke in Irish Sheep: prevalence and associations with management practices and co-infection with rumen fluke. Parasites Vectors 12: 525-539

- Jones et al (2017) Rumen Fluke (Calicophoron daubneyi) on Welsh farms: prevalence, risk factors and observations on co-infection with Fasciola hepatica. Parasitology 144: 237-247

- Sargison and Scott (2011) Diagnosis and economic consequences of triclabendazole resistance in Fasciola hepatica in a sheep flock in south-east Scotland. Veterinary Record. 168(6): 159-164