Garthorne Farm has been managed organically for the past two decades, with 100 per cent of the milk produced processed and sold direct to the public. Wendy Short finds out about its grassland management.

The 530-cow herd at Garthorne, near Darlington, County Durham, which produce the milk for products sold under the Acorn Dairy branding, is based on a three-way cross comprising Dairy Shorthorn, Swedish Red and Meuse-Rhine-Issel (MRI).

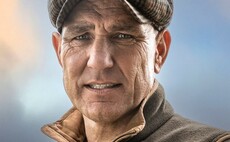

However, as company director Graham Tweddle explains, in recent years the Norwegian Red and Fleckvieh have replaced the Swedish Red and MRI respectively.

Mr Tweddle adds the all-year-round calving herd achieve 6,800kg from 1.4 tonnes of concentrate feed, with butterfat at 4.2 per cent and 3.8 per cent protein. They are also fed a total mixed ration including high-clover grass silage, haylage and wholecrop cereals.

Turnout is usually mid-March at Garthorne, which covers 283 hectares (700 acres). This is late for the region and is carried out very gradually to prevent the milk profile from suffering any rapid changes. Customers regularly come to witness turn-out and it is seen as an important event for involving them with the herd and the changing seasons.

A rotational grazing system is adopted, with a paddock size ranging from 1.2-4ha (3-10 acres). The plate meter is a key piece of equipment and is used with the aim of cows entering the paddock at just below 3,000kg of dry matter/ha and being removed at 1,200-13,00kg. The herd is housed in a combination of cubicles and straw yards from late October.

Mr Tweddle, who farms in partnership with his family, says: "There is a temptation to send cows back into a paddock to ensure that the right residual levels are achieved, but we cannot lose sight of the requirement to have a set volume of milk in the bulk tank to keep the dairy supplied.

"We are not always brave enough to shut fields up when the covers get too high and we are not keen on making small numbers of round bale silage. Therefore, paddock dry matters may end up above the target."

Without recourse to use herbicides, the Tweddles rely on topping thistles and docks after two paddock rotations and before they set seed. These are the two main problem weeds and other species are grazed off for control. If a field has been designated for wholecrop cereals, it will be worked with a stubble cultivator to allow frost to reach weed roots and kill off the plants before the area is ploughed and drilled in spring.

The stubble cultivator operation will be repeated following the wholecrop harvest and the machine will also be used at other intervals. The drying out of the weeds must take place over the summer, so the wholecrop is generally made with spring barley. This allows time to carry out the fallow work and for the following grass seed to be established.

Historically, some 20 per cent of the farm's grassland was replaced annually, but the family has found that using the right grazing species at the correct ratios will greatly prolong paddock life. Included in the mix are late perennial ryegrasses and festulolium, plus four varieties of white clover which make up 10 per cent of the sward. Plantain and chicory are also featured.

Mr Tweddle says: "There has been no reseeding for the past five years, as the areas are still fully productive and disturbing the soil would allow weed seeds the opportunity to germinate. The policy will only be reviewed if the paddocks fail to perform.

"The larger-leaved white clovers are very productive, but they are not particularly persistent and after four or five years will have died off. Meanwhile, the smaller varieties have greater longevity and they also fill the bottom of the sward. In a drought year, chicory may be the only green plant visible and it has a high level of minerals. It is extremely deep rooting and persistent, also acting as a soil conditioner."

The grazing paddocks do not receive applied fertiliser in any form. The sward is grazed fairly intensively and the cow dung is sufficient to maintain soil fertility levels. The whole farm is tested every 24 months and the indices hit the target, he adds.

Grazed clover is associated with bloat and Mr Tweddle admits that it requires careful management to maintain a healthy herd.

"We have learned that clover can be grazed as long as it is not too wet and if the cows have had a bite to eat before they are turned out. This is not a problem as we are normally buffer feeding to maintain the milk profile. The only times we have had an issue it can always be traced back to the cows being hungry before grazing."

There has been considerable investment in the cow tracks which lead to each paddock and these have been laid with various materials, including concrete, woodchip and Astroturf.

The 161-hectares (400-acres) of silage fields are made up of later perennial ryegrasses, the four types of white clover, some red clover and chicory and plantain. Both red and white clover make a significant contribution toward silage protein levels and the warming of the roots by the time third cut is taken turns the material into ‘rocket fuel, says Mr Tweddle.

Red clover is not sown for grazing, partly because the cows tend to eat it selectively and leave behind stalks and also because red clover must flower at least once in the season, he says. However it flourishes in dry conditions and helps to alleviate the compaction caused by silage-making and slurry equipment. Its use has removed the need for sub-soiling.

At the beginning of the season, the grass is top-dressed with either slurry at 15,000 litres/acre or composted farmyard manure at 8t/acre, with any remaining slurry used after first-cut. Farmyard manure is applied between the three silage cuts, but it is used sparingly as it can have a negative effect on fermentation. Rock phosphate is also applied, as well as a calcium lime where necessary, although the latter has not been needed for many years.

"The removal of grass from the silage fields will deplete the soil nutrition to the extent that it is difficult to apply slurry in sufficient quantities," says Mr Tweddle. "We also have to consider wind direction, as all the silage ground is next to residential housing and slurry smells are not always appreciated."

A silage inoculant is permitted under organic rules and it is routinely applied by the contractor. Mr Tweddle has firm views about the ensiling procedure.

He says: "Rolling is one of the most important aspects of silage-making in my opinion. A 14-tonne loading shovel is used, along with a 10-tonne tractor carrying 3t of weight. Rolling begins when the first load comes in and attention is paid to making sure that the entire surface is well-consolidated.

"We feel the clamp needs to be 100 per cent oxygen-proof and an oxygen barrier sheet is used under a Visqueen layer. Car tyres have been replaced in favour of specialised mats to increase the weight and coverage. They are spread over the entire pit."

Haylage is valued highly and has been grown since 2017. Mr Tweddle says: "A former silage field is set aside for haylage production. The presence of chicory does complicate the task as its large stalk is unsuitable and requires a prolonged period for drying.

"The intention is for haylage to replace costly bought-in organic straw. Another element is that straw has a comparatively low nutritional value; hay is higher in protein and with a longer structure that is better for the rumen. When making haylage we try to minimise moving the crop, which can cause leaf loss. It is made into big round bales which are chopped in the feeder wagon."

Many lessons have been learned since the farm was converted to organic production, says Mr Tweddle.

"Our aim is to try and produce as much home-grown protein as possible, partly because organic feedstuffs are so expensive to buy-in. This policy will also help to offset some of the wider issues associated with the dairy industry, by reducing the carbon cost linked to transporting food around the world.

"After 20 years in organic production, we have probably only accumulated a fraction of the knowledge that has been lost since my grandfather started farming and when all agricultural production was organic. I often wonder what agriculture it might be like today if agro-chemicals had not been introduced and modern science had focused on organic systems," he says.

Farm facts

- The family business is run by Graham Tweddle, his sister Caroline Bell and their parents Gordon and Linda Tweddle.

- The soil is a clay loam with a high sand content.

- The land sits at 60 metres above sea level.

- The herd cell count runs below 200.

- Apple cider vinegar is added to the ration to boost the immune system, while seaweed provides iodine and zinc.

- Sexed semen is used only used on the healthiest 100 cows (those which have never had mastitis or foot problems).

- Aberdeen-Angus and a small amount of British Blue used on the rest of the herd.

- The priority for bull selection is high health traits.

- Organic conversion began in 1998 and gave the direct sales business a unique selling point among its rivals.

- Acorn Dairy has 12 night time delivery rounds which serve Darlington (population 100,000) and the surrounding area.

- Other groceries like orange juice and cereals are offered on the rounds.

- The Dairy also sells milk, cream and butter to shops, catering establishments and schools from Morpeth to Leeds. Routes to Manchester and London have recently been added.

High yielder total mixed ration

First cut silage - 22kg

Third cut silage - 22kg

Ground maize - 5kg

Soya - 1kg

Hay - 1kg

Apple cider vinegar - 100ml

Seaweed - 100g

High phosphate minerals - 100g

Third cut silage analysis

DM - 35.1 per cent

Protein - 20.5 per cent

D-value - 69.3

ME - 11.1

pH - 4.1